After Monte Cook left Wizards of the Coast, he soon founded Malhavoc Studios, which was an independent RPG design studio that nonetheless published works through the D20 imprint of White Wolf (the World of Darkness folks), Sword & Sorcery Studios. Malhavoc became immediately successful, at least by the industry’s standards. Which wasn’t a huge surprise, given that most of its early works were written by Cook himself, who had risen to more widespread fame in the hobby due to his work co-creating third edition D&D, in addition to some other excellent releases and regular columns focusing on the art of DMing in Dragon and later Dungeon magazines. As a player during this era, I considered him bar none the most creative and interesting designer working on D20 content, and, well, despite his detractors I still consider this the more or less the case. Malhavoc’s work isn’t for everyone, but for people looking to push the bounds of D20 fantasy it rarely disappoints.

In 2001, Malhavoc came out with a bang by releasing the first commercial RPG book exclusively available as a PDF, The Book of Eldritch Might, which spawned many imitators, though none that I’m aware of which were nearly as successful. Of the company’s releases, I was particularly enamored of Arcana Evolved and Ptolus, both of which I used as resources for a campaign I ran for a few years right before entering grad school. I’m not going to launch into a full history of the company, which put out a lot of books ranging from a complete revision of D&D to adventures to more traditional supplements, except to say that they created a lot of excellent content in a short span of time, much of which would still be quite easy to convert to fifth edition or first edition Pathfinder (I’m yet to play second edition Pathfinder and generally have the sense it doesn’t integrate terribly well with most D20 material, but I could be wrong). Most of their books are long out of print in hard copies, but still easily available for sale in PDF form. The exception to this would be the massive, nearly 700-page Ptolus tome, which can be pre-ordered in a new fifth edition D&D or Cypher System (Monte Cook Games’ rather nifty proprietary-though-open RPG system) copy. If I had even a modicum of free cash I’d make this purchase myself, as MCG has an excellent track record with everything they’ve published so far and I’m a big fan of this setting, though alas, unless writing or editing somehow transform into a reasonably employable profession I’ll have to give this new version a miss.

Enough of me gushing about this somewhat obscure corner of gaming history, let’s get back to the topic at hand. In 2004, Malhvoc put out a book titled Beyond Countless Doorways that acted as a pseudo-reunion for designers and artists from Planescape. I suspect the inspiration from this came from an earlier work Cook wrote, Book of Eldritch Might III: The Nexus, which despite not being planar in nature was still focused on profiling unique locations that might be used for roleplaying games. The Nexus itself was adapted into BCD, and retconned into being a bit of an interplanar crossroads with some similarities to Sigil. Beyond even this, other works Malhavoc published were at least tangentially planar in nature, such as Anger of Angels, and it felt like BCD was a culmination of these impulses to return to the multiverse.

That being said, BCD is definitely not a Planescape book. Given how friendly Cook was with Wizards even after his departure from the company (I’m not an insider, I’m just aware that not only were Wizards employees like Bruce Cordell and Mike Mearls also writers for Malhavoc, others such as Michele Carter and Chris Perkins were known to play in his games), I suspect he probably could’ve managed to license that property and create a proper Planescape supplement at the time had this been his goal. After all, Wizards licensed out both Dragonlance and Ravenloft, and both of those settings were far more successful and lucrative. However, that was never his goal, neither was it to create a sort of pseudo-Planescape competitor. Instead, he wanted to create a more capacious work that included planar ideas which would never fit into such a rigid structure, be that Planescape’s defined cosmology or any other. The BCD cosmology would instead consist of infinite possible planes, such that there would be no limitations to where an RPG campaign might go.

That being said, BCD had two main things in common with Planescape, both of which make it a worthwhile read and something I absolutely didn’t want to ignore for this series. The first is that it contains the same unbridled creativity as the best Planescape releases did back in the 90s, filled with ideas for how a fantasy roleplaying session can feel radically different from a cliched Tolkien-esque affair. The second was that in order to make this new planar vision a reality, Cook assembled a murderer’s row of talent drawn from the original Planescape creators, himself included.

The actual book’s design is credited to Cook, Wolfgang Baur, Colin McComb, and Ray Vallese—three of whose names you might remember from an interview featured on this very site. The odd man out would be Baur, who despite my personal neglect is perhaps the most well-known of these designers, even eclipsing Cook. After leaving Wizards, he went on to found Kobold Press, an extremely successful publisher perhaps best known for their Tome of Beasts and Creature Codex accessories, though in fact they were licensed to design several officially released Wizards products for fifth edition including The Rise of Tiamat and Hoard of the Dragon Queen. Like Cook & Co., he’d officially left Wizards long before BCD, but still worked as a freelance designer, and this isn’t the last time we’ll see him mentioned in this series.

However, those weren’t the only ex-Planescape creators Cook roped in for his new book. BCD‘s forward was written by David “Zeb” Cook, the setting’s original designer, and its cover illustration is by rk post, who worked on numerous late releases for the setting after Tony DiTerlizzi was beginning to move on. Vallese also worked as one of the releases’s two editors, which is fitting since that was his primary role for Planescape, while the setting’s other primary editor, Michele Carter, proofread the book. Finally, playtesting is credited to Carter and fellow Planescape alumni Bruce Cordell and Chris Perkins. Obviously there are many contributors to the setting missing here, but considering that this was just a single book that’s quite a reunion. And fortunately, the resultant work lives up to its heritage.

Following Zeb’s forward, which I appreciated the inclusion of even if it didn’t really feel necessary, the book’s introduction and first chapter go through the basics of its expansive cosmology, as well as some ideas about how to use this book with D&D‘s core cosmology or any of your own. The thrust of all this is that there’s no reason this book can’t be used for practically any setting, it just might take a little bit of alteration to make it fit precisely with your needs. BCD‘s cosmology is that there are countless worlds, including infinite parallel planes and versions of what we might think of as heavens or hells, or energy planes, or whatever else. There isn’t any real guiding vision behind these, at least none that anyone knows about, and the division into hells or elemental planes etc. are just a way for people to categorize things— planes in and of themselves don’t give a crap about that kind of nonsense. They simply are. Slightly less interesting to me are the book’s ideas about planar conjunction and severance, but whatever, they’re also hardly relevant and easily ignored unless you want to be strict about your use of BCD‘s cosmology.

The question is then asked how people get around in this cosmology, considering that Sigil is owned by Wizards and not a part of this world. Some of the included ideas for natural planar rifts are pretty much what we saw in Manual of the Planes, but there are also several new methods listed, or at least “new” in that they weren’t part of D&D proper. The Nexus from Eldritch Might III makes another appearance, and now acts as a sort of replacement for Sigil, retconned into no longer taking people to various locations within a world but instead to locations in all worlds. In addition, there’s also a fully new (I believe, at least) way of moving between the planes through a place called the Underland, a ship that travels the planes, a new version of the Ethereal/Astral planes called the Ethereal Sea, and the Celestial Sea from Book of Hallowed Might II: Portents and Visions. In all, I would summarize the book’s first chapter by saying that DM’s should do as they wish with this and any cosmology and really go wild with the possibilities.

However, the cosmology and getting around it isn’t the real meat of the book, which is chapters 2-19, all of which spend their pages profiling single planes. Depending on the content this may include maps, NPC’s, items, spells, or anything else that might be useful. The planes included are only consistent in their inconsistency; some would make a great place to run an entire campaign, while others seem only suitable for a session or two at a time. But none of them are strictly speaking normal. Each chapter was written by one of the book’s four authors (I believe Cook wrote chapters 1 and 20 as well, but I have no actual evidence for this), and as a result they’re extremely varied with each author’s personality coming off strongly in their particular chapters.

The only way I can see of giving this work the respect it deserves is to write about each of these planes in kind, so if that’s not interesting to you feel skip to the bottom of this essay for concluding thoughts. This is going to be quite a lengthy write-up, as I’ll try to summarize each of these planes while also inserting a few bits of commentary about each one, but overall I recommend checking the book out yourself to see which parts you like best. Whenever the information was available, I’m also going to identify the author of the chapter in question, though in a few cases, such as with the first plane in chapter 2, I was unable (I could tell you who I believe wrote it, but that seems like a poor idea).

“Avidarel, the Sundered Star” is one of my favorite parts of the whole book, focusing as it does on the death and rebirth of a single plane. As noted by the write-up, the most obvious adventure here is simply to figure out how to bring the plane back to life, but beyond this it’s an interesting location to explore, consisting of a shattered sun and a handful of remaining mortals wondering what might come next. It’s one of those concepts that feels like it should’ve been played with before, as the death and rebirth of an entire world seems ripe with possibility, but this is the first time I ever saw it actually developed, let alone done so well. It’s a different sort of post-apocalyptic world for players to explore than something like Dark Sun, both bleaker and more hopeful at the same time.

Colin McComb’s “Carrigmoor” offers a completely different take on a planar apocalypse. Once a thriving interplanar metropolis, now Carrigmoor is one of the last cities of its plane, existing on an asteroid circling the planet’s old core. Adventures here are going to be slightly space-themed, with issues like breathing the atmosphere outside of this city. The plane itself isn’t disappearing here, but a plague caused the downfall of this realm and as a result the city is a cesspool. Carrigmoor probably suffers a bit from following Avidarel, as its post-apocalyptic remnant isn’t quite as alien or interesting to me, though on the other hand it’s a much better setting for an entire campaign. The city isn’t detailed by Planescape standards (though compared with Sigil, few are), but its map and profiles are more than enough for a DM to start with, and seems like a more interesting place for a vaguely space-themed fantasy adventure than Spelljammer does, filled with underhanded politics and a grubby population vaguely reminiscent of Sigil’s in its desperation.

Monte Cook’s “Curnorost, Realm of Dead Angels” is another bleak location, though in this case it’s more-or-less by design rather than the result of an apocalypse. The spirits of celestials head here for their afterlives, but because such a concept is in itself depressing, it’s not a place many will want to visit. At the same time, it offers one of the few possible methods for speaking with dead celestials, not to mention the resting place for the valuables they carried on themselves before death. It’s more of an alien realm to visit as part of a related campaign, and with this offers a great opportunity to change tone. More than perhaps anything else in the book, it’s very easy to see how to insert this into an ongoing adventure, and feels almost tailor-made as a solution to certain story problems.

“The Crystal Roads of Deluer” is the other chapter whose author I’m unsure of, and perhaps more importantly, it ended up being the most funny read of the entire book because my brain decided to pronounce its name as “Delaware.” It’s an earth elemental plane, inhabited mostly by xorn and made up of planetoids connected by crystal roads in an empty void. This offers a neat twist on earth/mineral planes, and I can see using it as an alternative to what’s found there in the core cosmology. However, aside from trying to loot the place and then running from the local xorns and elementals, it offers up fewer possibilities than pretty much everywhere else in the book.

“Dendri (Expansion 11)” by Ray Vallese is one of the absolute best new planes, taking a somewhat alien concept from Planescape and really running with it. This plane was once dominated by aranea, i.e. intelligent, shapechanging spiders. That changed, though, three years ago when formians discovered the moon they live on and began an all-out invasion. While this may sound like the location for a simple conflict, it’s made complex by the fact that the formians’ success is largely a result of the other creatures from this plane allying with them, after being previously abused and enslaved by the aranea. It’s a conflict with no good guys, and the setting brings in questions about colonization rarely asked by fantasy gaming, or any other gaming for that matter. Players can easily ally with either side here, and in a sense whoever wins the other locals, including grimlocks, elves, and hobgoblins, are going to suffer. I also find the entire formian conquest part of their species an interesting thing to play with, and was glad it got picked up by one of the authors here. Remember when formians were those peaceful ants on the cover of the Arcadia book in Planes of Law? Yeah, that isn’t these guys.

“Faraenyl” by Colin McComb explores a concept frequently seen in sci-fi stories, but not so much in fantasy. It focuses around a deceptively good place, a utopia of sorts, and then leaves the protagonists to discover what it is that’s wrong beneath the surface. It turns out that this extremely lawful plane, carefully divided between season-themed areas of land, is more or less powered by the deaths of its rulers. In essence, the plane allows for a more generic faerie-based setting to become something more interesting, and seems like a great place to center an entire short campaign around. It also makes me fantasize about living in a world where the rulers care enough about their subjects to die for them… now that truly is a fantasy.

“Burning Shadows of Kin’Li’in” by Monte Cook is a hell plane, entirely underground and filled with geysers of both fire and frost. The world is wracked by a war between those who worship fire and those who worship frost, and the all-out gang war between these two demonic factions controls the whole world. In addition to the demonic wars, there’s a weird shadow plague infecting the entire plane and making it so that every day there’s a 1-in-6 chance your shadow comes alive and tries to kill you. One of the main hooks here is to revive the dead demon prince who used to rule the plane, which, umm, like most things going on in this hell is not something I’d ever want to attempt. Basically, if you wanted a new layer of the Abyss, this one fits the bill quite well, and is more detailed and interesting than almost any we’ve seen before.

Wolfgang Baur’s “The Lizard Kingdoms” focuses on an alternate world where ogre-sized lizardmen and human-sized kobolds are the dominant races, while mammals and their kin are struggling for survival on the fringes. If you wanted to have a dinosaur-heavy campaign without setting things in a weird Fred Flinstone-style prehistoric setting, here’s your chance. While at first this concept didn’t interest me much, as its simplicity is obvious, Baur gives the chapter so much detail that I nonetheless wanted to play a campaign in this strange world. At 14 pages it’s one of the longer write-ups in the book, and takes the time to explain local politics for more than a dozen different factions. Essentially, this plane could’ve easily been its own campaign setting, and even in this reduced form it’s a worthwhile place to read about.

“The Maze” by Colin McComb may sound like something from Planescape, but is quite a different take on what interplanar mazes can mean. What appears to be a town surrounded by a maze leading to great treasure in different lands (it ventures through other planes) turns out to be a cursed realm tapping into the tortured mind of a trapped angel. Demons use this maze to hunt for prey, and create new pathways in the maze by stimulating the angel Sophiel’s brain with “varied venoms and psychic scents.” McComb offers up some sample journeys through the maze, and also reveals how this underlying secret can become part of a campaign to free the angel. It’s a very cool concept as a whole, and another pull-the-rug-out-from-the-players situation like his earlier plane Faraenyl, though in this case it plays off D&D game tropes in clever ways.

“Mountains of the Five Winds” is another chapter by McComb. This plane is caught between a realm of pure chaos and forces brought to fight against it from a plane of pure law. The problem is that most people are neither of these two extremes, and on much of the land itself those who chaos has made alterations to have taken over the joint. If you want to play out a chaos vs. law scenario in one plane rather than many, this is a good option, with quite a bit of detail, and like with Dendri it’s quite easy for players to ally with either side. In general I found Planescape’s version of these concept more epic and all-encompassing, but still enjoyed reading through this section for a somewhat different take on this conflict.

“Ouno, the Storm Realm” by Wolfang Baur is one of the odder planes in the book, and so feels like a great spot for an interplanar adventuring group to stop by for a few sessions. Here, the entire ground level is ruled by a sentient, godlike being known as Mother Ocean, and rain is acidic. Inhabitants travel in flying ships moving among islands that float in the air. Weirdly, drinking from Mother Ocean’s bounty leads people to become connected with her, which also means gaining psionic abilities, at least temporarily. In essence, it’s a place for swashbuckling air pirates with a few additional odd twists added to keep players on their feet.

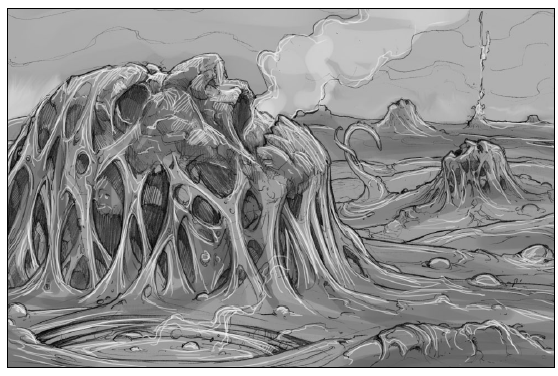

Vallese’s only other chapter is “Palpatur,” a formerly sentient plane that used up much of its strength to keep its inhabitant population of tieflings from harm. Now it’s a post-apocalyptic wasteland, with no trees, grass, or vegetation, and composed of a strangely artificial and gelatinous form of earth. The thing is, Palpatur is still alive, just unconscious, and its inhabitants (at least some of them) are interested in waking the plane back up. It’s one of the more alien locations in the book, and most tieflings still living here make their homes in the gigantic humanoid faces that erupted when the plane tried to smother a pair of invading devilish and demonic armies. One thing I like about this post-apocalypse is that for once everyone isn’t a complete dick here, they’re just in a difficult situation, which means that there are more possibilities for a campaign in this location than just figuring out who to fight next.

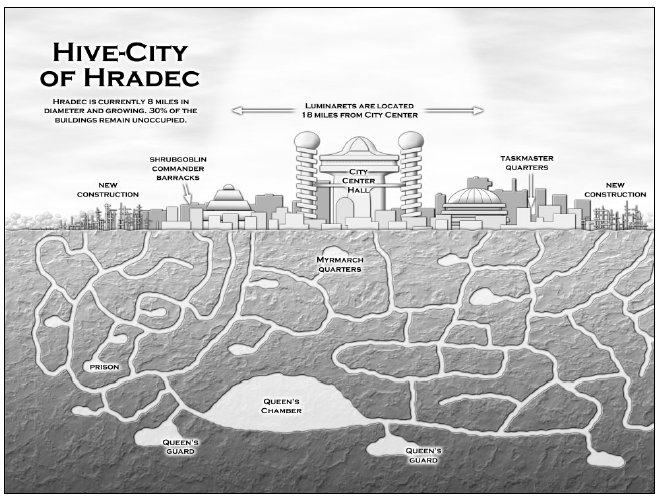

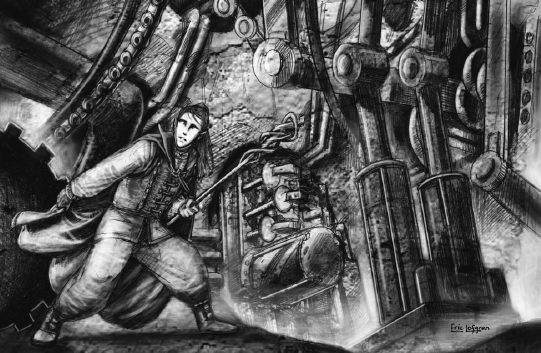

“Sleeping God’s Soul” by Cook is a related realm. Like Palpatur, at first this plane appears to be a realm of nothingness, but beneath its surface lies nearly endless clockwork caves filled with working gears, pumping pistons, and moving belts. When a lawful goddess first arrived, she made the plane her home. However, an enemy chaotic god pursued her here, and she was forced to hide underground. Drained of her power, the lawful goddess slept, and her subconscious created the complicated network of caves. It’s another location that seems better for a few adventures rather than a whole campaign, but seems like a fun place for interplanar travelers to stumble upon. What can I say, Cook likes his gods incapacitated.

“The Ten Courts of Hell” by Wolfgang Baur offers up essentially a different spin on what Hell can be in any cosmology, and these courts are essentially what Planescape would call layers. The courts are ruled by Yama Kings, who punish all who enter (mostly through abduction) with various hellish tortures. For the most part, its uses are the same as the Nine Hells of Baator, but with a slightly more Japanese flavor and a different convoluted series of rules. It’s a detailed, surprisingly deep write-up, but at the same time I’m not sure what this contains that the core cosmology doesn’t, making the Ten Courts one of the few chapters I can see skipping. I still enjoyed reading about the plane, but it’s just not unique enough for me to see returning to it for anything except its new demon statblocks.

In “Tevaeral, Magic’s Last Stand” by Cook, the last remaining spellcasters of the world have banded together in a small enclave, fighting for their lives against a land full of witch hunters. That being said, it isn’t just that they’re being attacked by random bigots, magic is literally disappearing from the plane, such that higher level spells are gradually fading from existence. Players get involved with this conflict, and may learn that magic’s death isn’t a natural thing but actually a problem caused by the extinction of dragons in this world. Only one still lives, and his death may mean the end of all magic (or the reverse…), though no one actually realizes this. I’m not sure that this setting could work for an entire campaign, which is true of most of Cook’s contributions to the book, but I do like the overarching scenario and think it’s a worthy place for players to step in and try to help out an ailing world.

“Venomheart, Haven of the Sleep Pirates” by Cook is an odd plane in that it’s mostly uninhabited. It really is just the haven for a single band of interplanar pirates, who go around stealing sleep from the rich and powerful because, umm, that’s what they’re into, I guess. While details about this plane are included, the chapter is more focused on profiling the pirates and with this offering a framework for players doing some interplanar piracy of their own, whether as part of Harvock’s band of sleep thieves or not.

The strangest plane in the entire book, by intention, is “The Violet” by Cook. As the result of a war between gods, a bubble plane of wrecked spacetime was created in which magic, time, and gravity don’t work as normal. The entire plane exists within a hollow sphere of solid ground, with long vines growing across it used for transversal since there’s not even subjective gravity available. Occasionally time rewinds for a random period, and perhaps most annoying of all no spells or magical effects above level one work anywhere in the plane… unless people are smart enough to create an “inverse antimagic field” and do their spellcasting within these areas. Because of its magic suppression, The Violet is primarily a prison plane, and as such Cook includes details on three such possible cells as adventure seeds.

The final chapter profiling a plane is “The Primal Gardens of Yragon” by Cook, which is one of the most sci-fi inclusions The world is ruled by giant, aggressive apes who spend their free time raiding other planes and grabbing slaves. Except the apes are in fact being controlled themselves by a virus called alaptur, who still effects and lives parasitically on these apes, but can no longer control them. Obviously stopping the interplanar slavery would be a good thing, and one way of doing this would be to destroy the alaptur, which isn’t hard to do once the virus is discovered due to how easily clerics can solve this problem, though this also removes the apes’ intelligence and leaves them as animals. It’s not the world’s most difficult ethical dilemma, but there is something interesting going on here, and it seems like another good place for planar explorers to stop by and assist while they’re traveling the multiverse.

Whew, that’s a whole ton of planes, and the book doesn’t end there. Its final chapter, “Through the Looking Glass,” considers possible parallel worlds for PCs to visit. It’s not as creative as the rest of the book, but does put an emphasis on usability and making these places fun for both players and dungeon masters.

In addition to all of these full write-ups, Beyond Countless Doorways also includes dozens of blurbs about other planes currently in conjunction with the ones here. Some of these feel like they’d make for even better adventuring locations than the planes actually detailed, and this goes along well with one of two pieces of web content Malhavoc published in support of the book, “101 Planar Ideas,” many of which tie in with BCD‘s planes.

Like with any collection of works, quality isn’t going to be uniform for BCD, though I doubt many will agree on which chapters were their favorites. Nothing included is half-assed, it’s just that some chapters are going to be more interesting to you than others, which is inevitable. If you are keen on interplanar adventures, you’re essentially guaranteed to find something worthwhile, and likely many chapters you’ll wish to add or adapt into your own campaigns. It is, simply, a good book full of good content. When I first started reading it for this column, I thought I’d go through it as quickly as I do most D&D books, but instead it took me weeks to get through, as I enjoyed slowly reading each chapter and thinking about its content. The prose and ideas throughout are refreshingly good, and it’s an excellent reminder of why planar material can be such a joy to read.

As far as production goes, the book is in black-and-white, which is only to be expected in order to make for an affordable product. The artwork is usually just ok, and rarely memorable, but that’s also typical for RPG supplements. Cartography fared a little bit better, and I actually prefer it in this regard to most contemporaneous work from Wizards. Overall design is a bit sparse, but this makes for a clean read, and I appreciate not trying to recreate Planescape in this respect. With its hardback binding, the book still looks good on my shelf today after all these years, even if the interior can feel a tad low-rent given how spoiled we all are with full-color D&D releases from Wizards.

The other bit of web content released to support BCD was a four-page (well, five, but an entire page is devoted to the OGL) write-up by Cook of what would happen if a world came in conjunction with an energy plane called Karlectash. Karlectash itself is uninteresting, just a blank void of alien energy. However, when it comes into “true conjunction” with another plane its energy wrecks havoc on the locals. Everyone on the touched plane receives an energy blast, in some cases killing them and in others transforming them into weirdo bug creatures called karlectars. It’s a worthy idea, but not fleshed out enough to really warrant interest for most DMs, and also only makes much sense if you’re using BCD‘s particular cosmology.

Beyond Countless Doorways is only one of many third-party D&D/D20 supplements focused on interplanar adventuring. Many of these are probably quite good, including Mike Mearls’ “Portals and Planes,” which maybe I’ll one day cover in the future for this column, but the sheer number of D20 releases means this isn’t a project I’m terribly interested in. However, BCD is something special. The quality of its content and the team who assembled it makes this a unique work in the game’s history, and well worth reading even if you’re only interested in the official Wizards of the Coast canon. No, it’s not a Planescape book, but it captures the setting’s spirit more than anything else released since that setting’s demise, and is a worthy successor throughout.